Wildlife

BLUE SHEEP (Pseudois nayaur) –DISTRIBUTION STATUS AND HABITAT ASSESSMENT IN SHIMSHAL VALLEY

Pseudois nayaur (Blue sheep) is native to Asia, and it characterizes as the “Least Known” by IUCN in the world and “Endangered” in Pakistan. This study aims to assess the distribution status and habitat assessment of the specie in Shimshal Valley, District Hunza Gilgit-Baltistan.

A Fixed-Point Direct Count Method has been used to assess the population trend of the species, while the Line Transects and Quadrat method was used to figure out the floral diversity in the habitat range of blue sheep.

Blue sheep, commonly known as Naur or Bharal, is a central Asian ungulate native to Asia. It is a constrained geographical distribution showing unclear phylogeographic and morphological structure variations. Among the most crucial habitat of the blue sheep are the Hindu Kush, Karakoram, and Pamir Landscape. In the IUCN Red List data, the Blue Sheep is placed under the status of “Low Risk/ near threatened”. However, in Pakistan, the species is considered Endangered.

The study area was Shimshal valley, located in Tehsil Gojal (Upper Hunza), with the nearest (62 km) town Passu, in District Hunza of Gilgit-Baltistan. The valley is spread over an approximate size of 3,800 km2, having around 2000 inhabitants living in 250 houses. The valley is divided into three different settlements – Aminabad, Center Shimshal, and Khizarabad.

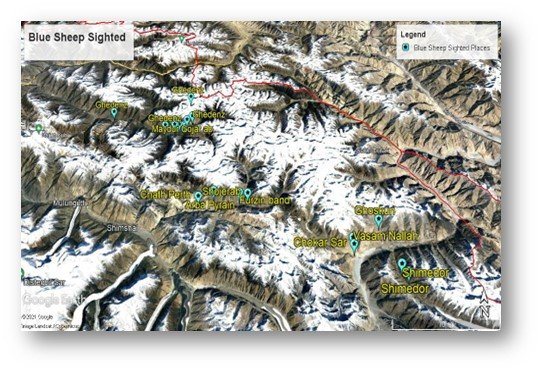

During the field survey, 625 Blue sheep in 24 herds at 13 different locations with a mean group size of 26 animals were sighted in Shimshal valley, district Hunza, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. The highest number of blue sheep herds were sighted at Maydur Gojarab (7 herds), followed by Ghendez (4 herds), and Shemedor and Arbab Pyrain (2 herds each), while at the other sites, only a single herd was witnessed. The biggest herd with 103 individual blue sheep was found at Shojerab. In comparison, smaller herds with 5 individual blue sheep were recorded at multiple locations including Maydur, Gojarab, and Ghedenz in the valley.

In the case of blue sheep, all male species are considered Trophy size animals, who fall under the category of Class IV, and their ages range above 8 years with a minimum horn size of 25 inches. In the current study at Shimshal, valley figures show that all the surveyed sites contain at least a single trophy-size animal. Further statistics show 105 (i.e., 16.32 % of total sightings and 41% of the male population) are trophy-size animals. A higher number of trophy-size blue sheep were sighted at Ghedenz and the lowest number was at Shimedor

Assessing for floral diversity ten different flora species from the habitat range of blue sheep were identified which include Ephedra intermedia, Potentilla fruticosa, Artemisia maritime, Pennisetum flaccidum, Salsola nepalensis Grubov, Kobressia capillifolia, Anaphalis acutifolia, Fragaria vesca, Chesneya depressa, Carex viridula.

Blue sheep in Shimshal valley are perhaps the westernmost isolated population of sheep in the Himalayas. Moreover, the species is amongst the most preferred prey species for snow leopards. Wild ungulates are among the indicators of habitat quality, of their role in maintaining ecosystems and affecting the diversity of plant species.

Suggestions For the Conservation of Pseudois nayaur For the conservation of this species of ungulate, community-based conservation should be strengthened across its habitat, for this awareness should be raised among the local community regarding the importance of the species towards ecology and also its esthetic value of it.

Moreover, the trophy hunting program which is a key conservation tool that is being applied across Gilgit-Baltistan for the conservation and sustainable harvesting of wildlife should be revised in the case of blue sheep on scientific bases.

This article is a part of the MS Thesis accomplished by Mr. Hassan Abbas under the supervision of Dr. Shaukat Ali, Associate Professor, and Chairperson, Department of Environmental Sciences, KIU, Gilgit.

Wildlife

Snow Leopard: The Mountain Ghost

Knowing about our natural treasures

“Wisp of clouds swirled around, transforming her into a ghost creature, part myth and part reality”, remarked by George B Schaller – a US based senior conservationist – when he came across a snow leopard just 150 feet away amidst the sheer wilderness in mountains of northern Pakistan, which he named as “the stones of silence”.

Introduction to the Snow Leopard

Snow leopard (Panthera uncia), also known as ‘mountain ghost’ is the most charismatic and elusive large wild cat in the Asian highlands.

Challenges Faced by Snow Leopard Populations

Its global population comprises only 3500-7000 individuals, presently occurring in Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Nepal, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. It has always been a challenge to maintain snow leopard populations due to its habitat overlapping with agro-pastoral activities of mountain dwellers. Habitat fragmentation is a common problem across all the range countries.

Snow leopards naturally prey upon wild goats and sheep found in the range areas but due to scarcity of natural prey they descend down to attack on domestic livestock including cattle, yak, goats and sheep, resulting in retaliatory killing by herders. One of the reasons for reduction of wild prey is illegal/subsistence hunting. Rampant hunting by poachers for use of body parts in traditional medicines in some parts of the range countries was also a big challenge to snow leopard populations.

The Snow Leopard in Pakistan

Pakistan’s population of snow leopards comprises about 350-600 individuals, mostly found in the northern mountainous region, known as Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) and Chitral. The region is the land of highest peaks including Mount Godwin Austen or K-2 (28,251 feet), other four peaks above 26000 feet, and numerous above 20,000 feet, providing an ideal world for snow leopards.

Conservation efforts in Gilgit-Baltistan for Snow Leopards

Pakistan’s snow leopards have recovered from the brink of extinction, due to rigorous conservation efforts, initiated in the 1990s, by organizations like WWF and IUCN together with the government of Gilgit-Baltistan involving local communities. Initially, it was a real challenge to convince herders not to harm snow leopards even when they would attack their livestock. For poor herders’ livestock rearing is the major source of livelihood and it was really a challenge to strike a balance between wildlife conservation and peoples’ livelihoods.

Community-Based Conservation Programs

Conservationists and policy makers with proactive involvement of local people in Gilgit-Baltistan introduced community-based conservation programs and initiated numerous conservation actions such as protection of wild prey, livestock insurance and afforestation schemes. For this purpose, community-based organizations (CBOs) were established at watershed/subwatershed level, ensuring representation of all households from that watershed.

The local hunters who used to hunt animals and birds for subsistence were employed under the community-based conservation programs as community wildlife watchers. Illegal hunting was banned and livestock grazing was regulated. The community wildlife watchers also kept an eye on locals to prevent use of poisons to kill large predators including snow leopards.

Trophy Hunting for Conservation

These community-based conservation efforts subsequently initiated trophy hunting programs involving protection of wild ungulates and offering few large male animals as trophies in the international markets.

Community-based trophy hunting of wild ungulates attracted hunters from across the world who pay up to $120,000 for a single trophy of Markhor (Capra falconeri – rare wild goat), $8,000 for blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur) and $3,500 for ibex (Capra ibex sibirica). 80% of the trophy hunting revenues go to the local community-based organizations and 20% to the government’s exchequer.

The community share is spent on paying community wildlife watchers and financing other socio-economic improvement initiatives such as provision of clean drinking water, micro-hydro electricity generation, afforestation, education and health support, etc.

Rescuing and Rehabilitating Snow Leopards

Another challenge was to rescue or rehabilitate injured or orphaned snow leopards in Pakistan. Hence one of an orphaned/displaced snow leopard cub, namely ‘Leo’ was handed over to Bronx Zoo in New York in 2005 for conservation and breeding purposes. The Leo recovered in captivity and had a cub in 2013 after breeding with a female captive animal namely ‘Maya’ in the Zoo.

Now the Gilgit-Baltistan government with support of conservation organizations has established a basic facility to take care of displaced animals. A female cub, namely ‘Lolly’ , recovered in 2012 from Khunjerab National Park, Gilgit-Baltistan is currently surviving in the newly established facility. However, the facility needs drastic structural improvements and financial support to be a state-of-the-art rehabilitation center.

At the time when the first cub “Leo” was handed over to the Bronx Zoo, the Gilgit-Baltistan government was expecting from conservation organizations to provide technical support in establishing a rehabilitation center.

Positive Signs of Recovery

Currently the snow leopard populations in Gilgit-Baltistan show a positive sign of recovering, which is evident from frequent sightings of the animals in different protected and community-based conservation areas. The wild prey species population is also increasing due to the ban on illegal and subsistence hunting, primarily due to trophy hunting programs, yielding socio-economic benefits for local people.

Expanding Protected Areas for Snow Leopards

More than 50% of the area in Gilgit-Baltistan has been brought under the net of Protected Areas.

Collaborative Conservation Organizations

Other organizations such as Snow Leopard Foundation, Pakistan (SLFP) and Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) are now actively working and supporting local communities to conserve the snow leopard and its prey species.

-

Tourism3 years ago

Tourism3 years ago15 Best Places to Visit in Skardu

-

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years ago

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years agoTraditional women’s dresses of Gilgit-Baltistan

-

KIU Corner2 years ago

KIU Corner2 years agoA Guide to LMS KIU Student Login – KIU

-

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years ago

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years agoShuqa Simple but amazing winter clothing of Gilgit-Baltistan

-

KIU Corner2 years ago

KIU Corner2 years agoEmbracing Challenges: Gul Rukhsar’s Remarkable Journey

-

Arts, Culture & Heritage3 years ago

Arts, Culture & Heritage3 years agoQuroot: A Nutritious and Flavorful Staple of Gilgit-Baltistan’s Cuisine

-

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years ago

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years agoTraditional houses Gilgit-Baltistan

-

Tourism2 years ago

Tourism2 years agoDiscover the Unparalleled Beauty and Culture of Gilgit-Baltistan