Opinion

Gilgit-Baltistan Marks 77th Liberation Day from Dogra Rule

Published

1 year agoon

By

Imran Ali

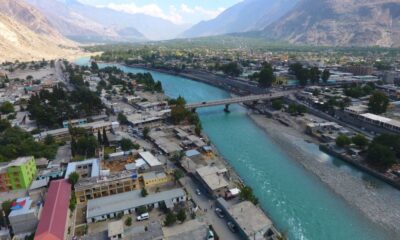

Gilgit-Baltistan enthusiastically celebrated its 77th Liberation Day on November 1st, 2024. A public holiday was declared in all ten districts, and various events were organized to commemorate the occasion.

The main event was held at Yadgar Shuhada Chinar Bagh, where Governor Syed Mehdi Shah, Chief Minister Haji Gulbar Khan, and Commander FCNA Major General Syed Imtiaz Hussain Gilani unfurled the national flag. Provincial ministers, the Chief Secretary, the IG Police, and other senior officials also attended the ceremony. Floral tributes were paid to the martyrs, and the armed forces of the GB Police presented a salute.

Governor Syed Mehdi Shah emphasized the sacrifices made by the Gilgit-Baltistan Scouts, the region’s forefathers to liberate it from Dogra rule. He also acknowledged the sacrifices of the martyrs and reaffirmed the commitment to national security.

A special Independence Day ceremony was organized at the Army Helipad, where high-ranking civil and military officials participated. For the first time in Gilgit-Baltistan’s history, the 77th Independence Day Parade was telecast live on national channels, including Gilgit-Baltistan PTV. Many people viewed the parade live at Wahab Shaheed Ground and Lalak Jan Shaheed Ground.

Commander 10 Corps Lieutenant General Shahid Imtiaz highlighted the significance of Gilgit-Baltistan’s freedom, achieved through the courage and sacrifice of its people. He emphasized the region’s enduring loyalty to Pakistan.

Chief Minister Haji Gulbar Khan paid tribute to the region’s martyrs and expressed pride in the people of Gilgit-Baltistan. He also acknowledged the pivotal role played by the Gilgit-Baltistan Scouts, a force with a rich history dating back to the British Raj. Their courage and sacrifice were instrumental in securing the region’s freedom from Dogra rule. Alongside the local populace, the Scouts fought valiantly against the Dogra forces and ultimately achieved victory.

The Independence Day Parade featured troops from the NLI Center, GB Scouts, Women Police, GB Police, Punjab Rangers, Cadet College Skardu, and Cadet College Chilas. The celebrations also included paragliding performances and cultural programs, featuring national and regional patriotic songs as well as local dances.

Similar celebrations were held in all districts of Gilgit-Baltistan, with cultural programs, flag hoisting ceremonies, and tributes to martyrs. The Pakistan Army played a significant role in organizing these events and broadcasting special programs.

As Gilgit-Baltistan commemorates its 77th Liberation Day, it reaffirms its commitment to national unity and prosperity. The region’s rich history, diverse culture, and stunning natural beauty continue to attract visitors from around the world. With its strategic location and abundant resources, Gilgit-Baltistan is poised to play a vital role in Pakistan’s development and progress.

About Author

Imran Ali

The writer is the Founder & CEO of The Karakoram Magazine. Additionally, he is a nuclear scholar fellow at the Centre for Security Strategy and Policy Research (CSSPR) and can be reached at aleee.imran@gmail.com.

You may like

-

Rumi, the Moral Psychologist

-

Poor Winter Maintenance of KKH Risks CPEC All-Weather Trade

-

Pakistan Army Launches Rescue Operation, Missing Passengers in Deosai Found Safe

-

PM Shehbaz Sharif Visits Gilgit-Baltistan, Honors Martyrs, and Launches Development Projects

-

CISS-KIU Seminar: A Tribute to Gilgit-Baltistan’s Freedom Fighters of 1947

-

A Tryst With History On The Karakoram

Arts, Culture & Heritage

Rumi, the Moral Psychologist

Published

1 year agoon

January 14, 2025By

Zameer Abbas

Maulana Jalal-ud-Din Mohammad (1207-1273), popularly known as Rumi, was a Muslim theologian-turned-poet. His poetry, published in two genres of masnavi and ghazal is mainly focused on the idea of love and its relation to the intimacy with God. However, the thoughts of Rumi, expressed through thousands of verses and ghazals, go beyond love and touch upon various aspects of human life and the universe. Even a cursory reading of Rumi’s poetry reveals his wide-ranging and thoughtful expressions on nature, universe, world, anger, lust, justice, purity, etc. According to Ahmed Javed, a contemporary literary critic, Rumi is the best author of human experience in the world. In other words, Rumi best describes the meaning of being a human on planet earth. Alan Williams, professor of Iraninan studies and translator of the works of Rumi, has identified the voice of moral reflection or homily as one of the seven voices while defining the narrative structure of Masnavi, a long poem by Rumi published in 06 volumes. Similar vein of advice and observations on moral psychology can be found in over 3,000 ghazals of Divan or Divan-e- Shams, the collection of ghazals by Rumi. Brittanica, an online encyclopedia, defines moral psychology as “the empirical and conceptual study of moral judgement, motivation and development”. This article details the verses of Rumi, from both Masnavi and Divan, which convey the deep observations of the poet regarding moral psychology. The verses are easily discernible for enduring reliability.

Like other poets, Rumi deploys the tropes of allegory, metaphor, simile, folklore, historical events, personalities, Quranic verses, Hadith etc to make his point. I will present a selection of verses from Rumi’s Masnavi and Divan highlighting the moral psychology therein.

این جہان کوہ است و فعل ما ندا

سوئ ما آید نداہا راصدا

(M I:215)

This world is the mountain, and our action the shout: the echo of the shouts comes (back) to us.

Rumi has explained the recompense for deeds and misdeeds by comparing the whole world to a mountain. Just like the mountain returns the schists by echoing it, the good and bad deeds are accordingly rewarded in this world.

Rumi’s places a lot of emphasis on the importance of thoughts in the life of a human being. He considers that a human being is nothing but a thought itself.

ای برادر تو همان اندیشه ای

ما بقی خود استخوان و ریشه ای

گر گُل است اندیشه ای تو گُلشنی

ور بوُد خاری تو هیمه گُلخنی

Brother! Your worth is in your thoughts alone; you are blood and flesh apart from that

You are rose, if all your thoughts are selfless

If bitter, you are a thorn that is judged worthless

Brother, your worth is in your thoughts alone

M II, 277-278

The formidable effect of a person’s thoughts are highlighted in the above verses. The precursor of every action is a thought. In a sense Rumi is ahead of René Descartes (1596–1650), French philosopher, by three hundred years who affirmed cogito ergo sum ( think therefore I am!). In other words, the ability to think and perceive constituted the most important element of human existence. At many places in both Masnavi and Divan Rumi elucidates how negative thoughts disempower and depress a human being and how he can rise above those thought processes. In the opening verse of Ghazal 2500 of Divan, Rumi diagnosed that the doom and gloom is always characterised by mean thoughts of a man:

چه افسردی در آن گوشه چرا تو هم نمیگردی

مگر تو فکر منحوسی که جز بر غم نمیگرد

Why are you depressed and cornered instead of moving ahead?

But then you are an epitome of mean thought and you are obsessed over grief

In numerous verses, Rumi emphasises the layered and unfathomable inner world of a human being, making it all the more important to avoid judging someone through appearances alone. An example:

َمرد را صد سال عم و خال او

یک سر ُمویی نہ ِبیند حال اُو

A man’s paternal and maternal uncles (may see him) for a hundred years, and of his (inward) state not see (so much as) the tip of a hair (M:3, 4249)

Rumi underlines the complexity of human psyche in that it is characterised by an inner world which is rarely apparent. In other words, he implies that our judgements based on the outward appearances or behaviour of a person may well be wrong considering that appearances never represent the human being on the whole.

Regarding worldly gains and glory, Rumi maintains that on the one hand they uplift and increase a person’s standing among the people but conversely they become the reason of the downfall too as succinctly expressed in the verse below:

دشمنِ طاؤس آمد پر اُو

ای بسی شہ را بکشتہ فر اُو

The peacock’s plumage is its enemy: O many the king who hath been slain by his magnificence!

(M1:208)

Rumi is of the view that by reciprocating a bad deed, one becomes equal to the perpetrator of the act. He, therefore, exhorts restraint or better still good behaviour in response to treatment.

گر فراق بندہ از بد بندھگی است

چون تو با بد بندگی پس فرق چیستHave I deserved my fate for some offence; If you hurt sinners what’s the difference?(M:1,1564)

It can be discerned from the above selection that besides numerous themes in his collection of verses (in Masnavi and Divan) Rumi conveys a message of morality in unmatched eloquence and clarity. Perhaps it is beauty and depth and a sense of wonder in these verses that remain relevant to date and keeps guiding anyone who immerses in the ocean of his wisdom.

About Author

Zameer Abbas

The author is an alumnus of the Institute of Development Studies, UK. He is currently associated with the government of Gilgit-Baltistan and tweets at @zameer_abbas21.

CPEC

Poor Winter Maintenance of KKH Risks CPEC All-Weather Trade

Published

1 year agoon

November 20, 2024By

Imran Ali

The Karakoram Highway (KKH), a vital lifeline for trade between Pakistan and China under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), faces critical challenges each winter due to negligent maintenance. Connecting the two nations through the Khunjerab Pass—at over 4,693 meters (15,397 feet) above sea level—this strategic route is central to trade and regional economic integration. The pass connects Gilgit-Baltistan with China’s Xinjiang region and was reopened after closing for almost three years in April 2023. The land border was closed in 2020 after the outbreak of COVID-19. However, when heavy snowfalls hit, KKH becomes treacherous, risking the disruption of trade and the economic ties vital to both countries.

The KKH, a pivotal component of CPEC, facilitates the movement of goods and strengthens economic ties between Pakistan and China. Its year-round functionality is crucial for trade. Yet, the lack of timely snow clearance and road maintenance is disrupting the route, undermining the goals of CPEC.

Despite past agreements aimed at transforming the KKH into an all-weather route, meaningful execution has been lacking. This year, authorities have announced plans to finally implement measures to ensure year-round connectivity. However, the existing state of road maintenance raises doubts about their effectiveness and commitment.

For Aman Ullah, a resident and trader from Gojal, Hunza, the snowbound Karakoram Highway is more than just an inconvenience—it’s a daily struggle that threatens his livelihood. “We are often left stranded for days, with no way to continue our trade,” he shared with The Karakoram.

Aman explained, “A few years ago, the Chinese government donated four state-of-the-art snow-clearing machines to the FWO for winter maintenance of the Khunjerab Border and nearby sections of the KKH. These advanced machines, equipped with computerized systems, were intended to ensure safe travel and uninterrupted trade. However, only one of these machines remains operational today, and even that is reportedly in poor condition. Instead of effectively clearing the snow, it often leaves the road even worse, making travel difficult. The fate of the other three machines remains unknown, raising serious concerns about mismanagement and a lack of accountability.”

The poor state of snow clearing operations has caused a worrying rise in road accidents, Tufail Ahmed, the owner of a transport company whose vehicles frequently travel to China via the KKH, shared his frustrations. Stranded vehicles have become a common sight, with travelers risking their lives in freezing temperatures,” he said.

Abdur Rehman, an import-export trader from Gilgit-Baltistan, highlighted the contrast between the two sides, adding, “In stark contrast, the Chinese side of the Khunjerab Pass ensures the road remains well-maintained and operational during winter. Advanced machinery and a proactive approach demonstrate their commitment to maintaining seamless connectivity. This disparity reflects poorly on Pakistan’s preparedness and raises questions about the efficiency of NHA and FWO.”

Dr. Faqeer Muhammad, Director of the China Study Centre in Gilgit-Baltistan, emphasized the broader implications, stating, “The KKH is more than just a road—it’s a vital trade corridor that plays a key role in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI); it is a symbol of connectivity, trade, and opportunity. Neglecting its maintenance during winter risks undermining Pakistan’s economic and strategic interests, calling for immediate attention from the authorities.” Its maintenance is critical not just for trade but for the broader economic and strategic objectives of CPEC.

This neglect not only puts lives in danger but also hampers trade activities, creating significant bottlenecks for transportation linked to CPEC.

Residents and stakeholders are demanding urgent action to address these issues. Effective utilization of resources, transparent accountability for the missing machinery, and better coordination between authorities are imperative. Maintaining the KKH as a safe and reliable trade route is not just a regional necessity; it is a cornerstone of CPEC and a matter of national importance.

About Author

Imran Ali

The writer is the Founder & CEO of The Karakoram Magazine. Additionally, he is a nuclear scholar fellow at the Centre for Security Strategy and Policy Research (CSSPR) and can be reached at aleee.imran@gmail.com.

Gilgit, a sleepy outpost at the heart of High Asia, plays a key role in shaping the region’s geopolitics over millennia— including the rivalry eulogised as The Great Game between the British and Russian Empires.

It was during the research for my manuscript, ‘The Great Gilgit Game’, that I came across a people with whom I share a regional ancestry – the Burusho community of Kashmir. Evoking a professional high, given its prospects of enriching my academic endeavour, the discovery also elicited a personal joy, as I conjured a sense of kinship and association – the desire for familiarity, of belongingness and ownership being key pursuits of those uprooted or isolated from their native cultures and domain. I was a Pakistani, living in India.

I had chosen to write about Gilgit, a sleepy outpost at the heart of High Asia, not only to pay homage to my roots and ancestry, but also as a revisit to the marvel that constituted its strategic geography, having played a key, even if little appreciated role, in shaping the region’s geopolitics over millennia – including the rivalry eulogized as The Great Game between the British and Russian Empires. Currently, as the border gateway to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the flagship enterprise of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the region is once again poised to become a key theatre of the evolving Great Power Competition, situated as it is at the crossroads of critical histories, geographies, rivalries and resources.

Amidst the churn of great power dynamics, why the banality of a small émigré community having captured my imagination? Stemming partly from the promise of a personal connect, it was the intriguing backdrop within which the migration took place that caught my attention. The migration in reality was a banishment, that of the reigning ruler of Nagar, a border pocket state situated on a tract of land famously described by the British traveler E.F Knight as “Where three Empires meet”. Nagar along with its sister state of Hunza, the fabled valley identified by many as the mythical Shangri–La of James Hilton’s ‘Lost Horizon’, occupied great strategic salience within the British imperial construct, especially as part of its Forward Policy against a perceived Russian onslaught on its northern frontiers in the mid-nineteenth century. The petty states of Hunza and Nagar were situated at the southern end of the Pamir Mountains in what today constitutes Gilgit-Baltistan— a part of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir. It also bound the neighbouring Chinese territory of Xinjiang (East Turkestan) and the Khanates of Central Asia— all annexed and under the patronage of Russia— hence the “meeting of the three Empires”. This further whetted the fear of what came to be termed as the “Pamir Gap”— the possibility of various passes along the Pamir and Karakoram mountains being used by Russian Cossack forces to launch an invading attack on India. Under these circumstances it became imperative for the British to secure key border regions and bring them directly under the Empire’s sway. This however, was not an outlook the rulers of the Hunza and Nagar states were receptive to, especially as Hunza, the bigger and more powerful of the two states, had already entered into a tributary relationship with the neighboring Chinese Empire. Besides, as autonomous states the rulers especially that of Nagar, the defiant Raja Azure Khan, were reluctant to surrender their authority and powers. The inability to reach an agreement over the issue between the two sides, subsequently lead to The Anglo-Burusho war of 1891. A bloody battle ensued and despite the brave front put up by the Hunza-Nagar forces, the superior British force imposed a crippling defeat. The importance of the campaign can be ascertained by the fact that three Victoria Crosses (VC) and numerous Indian Orders of Merit were awarded to the troops by the British Government. The fact that the British forces were led by Colonel Algernon Durand, the brother of then Foreign Secretary of India, Sir Mortimer Durand further underscores the significance of the campaign.

The British victory also sealed the fate of Raja Azure Khan, the incumbent Raja of Nagar, who was ultimately exiled to Kashmir. His pliant brother, Sikander Khan was placed on the throne instead, clearing the way for a smooth transition towards the British territorialisation, and hence domination of the region. In Kashmir, Azure Khan was initially imprisoned at the Hari Parbat fort, along with his supporters who were exiled with him. After six years of imprisonment, he was then shifted to a nearby estate and kept under house arrest. It was in March 1922 that Azure Khan breathed his last and was laid to rest in a mausoleum situated in the outskirts of Srinagar city. His offspring and those of his followers banished with him continue to reside in the city.

This fascinating piece of history piqued my interest both in terms of its historical gravity and the personal opportunity it presented to forge a connect. I had already known some of the offspring of the erstwhile ruler, without knowing the history, but as invested as they were within the structures of Kashmir’s elite socialization, there was little scope for the cultural identification I was looking for. I was somehow led to the set of descendants still living in the vicinity of the estate Azure Khan had spent his final years in and was taken aback at the laborious preservation of their erstwhile culture and identity. The conscious effort and perseverance in cultivating their roots was laudable. While I too traced my antecedents to Gilgit, I was not ethnically a Burusho. Nestled in the heart of High Asia, Gilgit had over millennia bordered myriad imperial territories, cultures and ethnicities, becoming a melting pot of the same. The northern territories of Hunza-Nagar bore heavy Central Asian imprints, while the southern territory of Astore, to which I belong, diluted the cultural impact of the region’s northern neighbours. Hunza-Nagar had also acquired the Pagan customs of the northern (Central Asian) steppes including the belief system of Shamanism which they continue to practice, albeit in a watered-down version, to date. A shared language, the great denominator, was also missing. The community spoke Burushaski, a language isolate spoken only by the people of Hunza-Nagar, whereas I speak Shina, the predominant language of Gilgit.

This however didn’t hold me back and neither did it deter them. I was invited for tea with the community. As I entered the hillock where the community largely lived – near Kathi Darwaza in downtown Srinagar, it was as if I was transported to the alleys of Gilgit. There was a certain character to the place that reminded me of home, whether real or imagined, but I felt an instant connect. Despite the passage of well over a century and four generations later the Burusho community continued to firmly hold on to their customs and ethos. Even the youngest generation communicated in fluent Burushaski and an evident sense of pride in their antecedents prevailed. This had however not kept them from assimilating into the larger society around them but there was a conscious decision to hold on to their ancestral way of life. I was shown photographs of weddings where the traditional Nagar practices and rituals were incorporated alongside the Kashmiri traditions. The grooms continued to wear the traditional Gilgiti outfit known as the Chogah. The men adorned the peculiar tilted woollen headgear referred to as Khoi in Gilgit—I remember my uncle gifting Khois to my young children on their last visit there, over a decade ago. The women also owned traditional Gilgiti silver jewelry having collected them from previous visits to Gilgit or received them as gifts from relatives in Gilgit during planned pilgrimages to Makkah together. Over the years communication had however become difficult as relations between India and Pakistan deteriorated. The anguish of the community over the inability to stay in touch with their loved ones was indicative of the plight of divided families separated by conflict.

Another means through which the community preserved its ethnicity was by instituting marriages strictly within the community, a practice especially espoused by the royalty. It was also a means of keeping their race ‘pure’. The practice had been instrumental in preserving the Central Asian physical features of the community characterized by a bright complexion with mostly blue or green monolid eyes, distinct from the aquiline nose and high cheek bone facial features of the indigenous Kashmiri race. Hence the sobriquet ‘Botraja’; Bota in Kashmir refers to people with mongoloid features, and raja means King. However, with time, inter-marriages have started to become normalised. Also, in a departure from their ancestors in Nagar, the community in Kashmir traces their lineage to Nausherwan Adil (Nausherwan the Just), one of the most venerated Kings of ancient Persia. Their counterparts in Gilgit however trace their antecedents to Alexander the Great, while some also establish heredity with fairies and deities – a reflection of their belief system centered around themes of the Supernatural. Gilgit has however appealed to such enthralling wonderments since times bygone, be it the “Gold-Digging Ants” of Herodotus or the site of the more scientifically proven tectonic collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates that gave rise to the mighty Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau – the highest in the world. Gilgit also houses one of the oldest and most diverse collection of petroglyphs (Rock Art) in the world and has been an important (southern) artery along the ancient Silk Road through which Buddhism spread to the East under the aegis of the Great Kushan King Kanishka via the passes of the Karakoram Mountains. The Karakoram Mountains and the Karakoram Highway that now traverses through it from the border with China in the north all the way to the warm waters of the Indian Ocean to the south, remains an intrinsic pathway for the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which has now assumed strategic significance well beyond just economics. The region is steadily emerging as an intersection where the India-Pakistan, India-China and US-China rivalries converge. The India-China border conflict of 2020, in close vicinity to the Karakoram Pass being one such representation. The region is very much on course to becoming the next hotspot as per Harold Mackinder’s Eurasian Heartland theory and the evolving Indo-pacific strategic architecture.

Having come across documents related to Mir Sikander Khan, the brother of Azure Khan who was made to succeed him after the latter’s exile, I became curious as to whether the paths of the brothers ever crossed again. One such early opportunity arose during Raja Sikander Khan’s visit to Srinagar in 1903 enroute Delhi for the Coronation Durbar, held to celebrate the succession of King Edward VII as Emperor of India. Upon inquiry, Raja Tasleem Khan, the great grandson of Raja Azure Khan, denied knowledge of any such encounters, more so as Raja Azure Khan was then being kept under house arrest while Mir Sikander Khan was visiting with official protocol. It became clear that there had been no interaction whatsoever, between the direct descendants of Azure Khan and that of Raja Sikander Khan. The two families had also followed different socio-political trajectories with the successors of Raja Sikander Khan having enjoyed state patronage in Pakistan as ceremonial rulers of the erstwhile state of Nagar, while those of Azure Khan led common lives in Kashmir. I also tried getting in touch with the incumbent Raja of Nagar, Raja Qasim Khan who now lives in London, to get his views on the subject and establish communication, if possible, between the two families. But to no avail.

Looking back, the saga of Raja Azure Khan has enabled me an entirely novel perspective, bringing closer to home the intricacies of imperial machinations. It has also drawn my attention to the power of the moment, how a defining decision or event can alter the course of history and the destiny of many. More so, the history of the region no longer remains a distant, blurred ideation for me, having acquired a life of its own with the real-life, personalized appreciation of its inner workings and the course it took. The family of Raja Azure Khan continues to remain a source of heartfelt camaraderie.

Asma Khan Lone

The writer is an academic. A graduate of the University of Cambridge, she has previously taught at Jindal Global University and is presently working on her manuscript ‘The Great Gilgit Game’ with Penguin India.

This article was originally published in Outlook India.

About Author

The Karakoram Magazine

The Karakoram Magazine seeks high-quality, unpublished,nonfiction, first person articles relevant to Gilgit-Baltistan and topics as varied as Geo Strategic & Economic Significance of GB, Arts & Literature, Tourism & Hospitality, Culture and heritage, Education and technology, Health & Wellbeing, Climate Change and Wildlife, Economic & Trade, Sports & Recreations, Youth & Women empowerment and Achievements of Illustrious People of GB in different fields etc.

Muhammad Azeem Khan: Pakistan’s Number One Amateur Featherweight MMA Fighter

A Drop for a Click: The Silent Cost of Our Digital Thirst

10 Places to Visit in Hunza – Stunning Natural Wonders You Can’t Miss

Latest

-

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years ago

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years agoTraditional women’s dresses of Gilgit-Baltistan

-

KIU Corner2 years ago

KIU Corner2 years agoA Guide to LMS KIU Student Login – KIU

-

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years ago

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years agoShuqa Simple but amazing winter clothing of Gilgit-Baltistan

-

KIU Corner2 years ago

KIU Corner2 years agoEmbracing Challenges: Gul Rukhsar’s Remarkable Journey

-

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years ago

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years agoTraditional houses Gilgit-Baltistan

-

Tourism2 years ago

Tourism2 years agoDiscover the Unparalleled Beauty and Culture of Gilgit-Baltistan

-

Opinion3 years ago

Opinion3 years agoExploring the Enchanting Astore Valley: A Paradise in the Himalayas.

-

Current Affairs2 years ago

Current Affairs2 years agoGilgit-Baltistan and the Geopolitics of the Third Pole