Current Affairs

Juglot – Skardu Road

Published

3 years agoon

The Strategic Vein and Lifeline of Baltistan

Highways are considered to be the basic means of modern communication and transportation systems. It is almost inconceivable to think of an area to be unconnected to the world and yet carry on with life. Life on earth depends upon basic means of survival – from basic food items to life-saving drugs as well as socialization with fellow human beings. The Baltistan region of Gilgit-Baltistan, also known as Little Tibet, is not an exception.

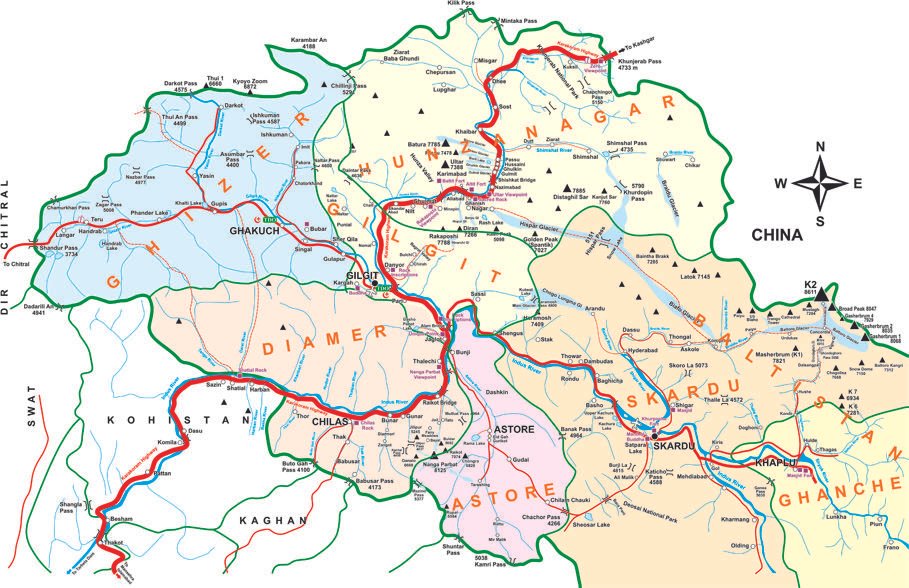

The North-eastern region of Baltistan houses almost one-fourth population of the Gilgit-Baltistan region. On land, travel becomes as treacherous as it could be because the region is parched between the Karakoram and Himalayan Ranges. Shortest access points to the region, termed as “passes” are either too steep to negotiate or too dependent upon weather conditions to frequent with ease, hence leaving with the only viable option to build a road through a terrain that is mountainous to the extent that a mere 167 kilometers stretch of road took twelve years to complete in 1982. On top of that, the loss of precious life made it even costlier.

Even after its completion in 1982, the Juglot-Skardu Road remained infamous for its unpredictability and jaggedness mostly owing to frequent road slides and tardiness of the workforces entrusted with the responsibility to make it travel-worthy year-round. The frequent commuters would bear witness to the unfortunate scenarios that, natural disaster aside, manmade delays were to blame equally for many a starvation-like situation in the region for the supply vehicles remained stranded on road for weeks and loss of many a precious life because the people at the helm of the affair would not order initiation of opening the blockades. This inhuman attitude had even resulted in scrimmages between the road workers and the commuters.

After a lapse of 40 years, the Juglot – Skardu Road is now realigned and it is perpetrated by the construction company that it is the highest standard highway which is constructed adopting the best international standards of road construction. It is too early to comment on the standard of the highway, but it can be safely said that the regular commuters are all praises for it.

The realignment has remarkably reduced the time travel. It is now taking less than four hours whereas the time of travel before the realignment was more than 7 hours provided that no obstruction hindered the drive. So, the reduction of three hours in the travel time is a relief.

The Juglot – Skardu Road is a relief for the general populace of Baltistan and the people GB frequenting for job and business purposes. The general populace is thankful because the realigned road has reduced the travel time and resultant cost saving. It is also a relief to travel on a much evener road for the frequent commuters. The transport companies are jubilant that they can save the cost of vehicle wear and tear.

The Highway from a Tourism Perspective

The Baltistan region of Gilgit-Baltistan is the epitome of natural beauty. The region is not only home to picturesque landscapes and historically significant architecture and artifacts, but it also boasts to be the gateway to mountaineering expeditions in the Karakorum Range, including the mighty K2, Gasherbrum I, Gasherbrum II, Broad Peak, and Trango Towers. It also paves the way through its magnificent valleys, the likes of Askole and Hushe, to the Baltoro, Biafo, and Trango glaciers.

Baltistan is also home to the Cold Desert, the highest desert in the world. This connection of roads is bound to benefit the Sarfaranga Desert Rally a great deal.

It is expected that with the improved road conditions tourism to Baltistan would boost manifold. It has been observed that domestic tourists now readily go to Baltistan for they do not fear standing on the road for days.

Moreover, the tourists who dread long road travel on Karakoram Highway (KKH)from Islamabad to Gilgit that can now take flights from Islamabad, Karachi, and Lahore to Skardu and from there could reach Gilgit and beyond within three hours whereas road travel on KKH takes almost 15 hours to reach Gilgit.

It is also convenient for the populace of other than Baltistan that they could reach Skardu in a couple of hours and take a flight to Islamabad and beyond without difficulty.

Strategic Connectivity

Baltistan’s four districts border with China and India through Karakoram Pass and Kargil, Daras, Siachin, Chorbut, and Batalik sectors, making it an area of strategic importance. Since the region is of immense strategic standing, the road would prove to be an asset in mobilizing armament to safeguard the motherland.

This extraordinary connection of highways and narrow paths not only leads to arresting scenarios, but it also connects the rest of the region to the likes of Siachen – the longest glacier in the Karakorum Range and the second-longest to fall in a non-polar region. The Highway makes it easier to access the strategic area, linking Pakistan to the Saltoro Ridge and the highest battleground on Earth.

Economic Potential of Baltistan

This strategic highway built across the once jagged stretch has opened up many ways to boost the economic potential of the region. Gilgit-Baltistan has been recording a substantial flow of tourists into the region and with the advent of the highway, this is further anticipated to increase. This will not only benefit the tourism industry in the region but also boost its economic potential to the maximum. With the Skardu Airport being upgraded to international standards of operation, international routes leading to the region serve as a major economic benefit.

However, there have been some observations as well. The initial design comprised of four tunnels where landslides damage the road now and then which has now been scrapped and that section of road is again prone to landslides. It is also being observed that some sections of the road have been repaved with a flimsy layer of tar and under this layer is the same old road. The road could include bridges despite the long and dangerous diversions on side valley tributaries of the Indus River is another critique.

Nevertheless, the Juglot-Skardu Road, the strategic vein and lifeline of Baltistan, has come to life. It is completely powered to provide the region with better tourism activities, the economic potential boosted to the maximum, and strategic connectivity more than ever now.

About Author

Lala Rukh Ramal

The writer is an associate editor at The Karakoram Magazine and is also pursuing a master’s degree in Chinese politics from the Silk Road School, Renmin University of China.

You may like

-

Rumi, the Moral Psychologist

-

Poor Winter Maintenance of KKH Risks CPEC All-Weather Trade

-

Pakistan Army Launches Rescue Operation, Missing Passengers in Deosai Found Safe

-

PM Shehbaz Sharif Visits Gilgit-Baltistan, Honors Martyrs, and Launches Development Projects

-

CISS-KIU Seminar: A Tribute to Gilgit-Baltistan’s Freedom Fighters of 1947

-

Gilgit-Baltistan Marks 77th Liberation Day from Dogra Rule

Current Affairs

Gilgit-Baltistan and the Geopolitics of the Third Pole

Published

2 years agoon

April 29, 2024By

Imran Ali

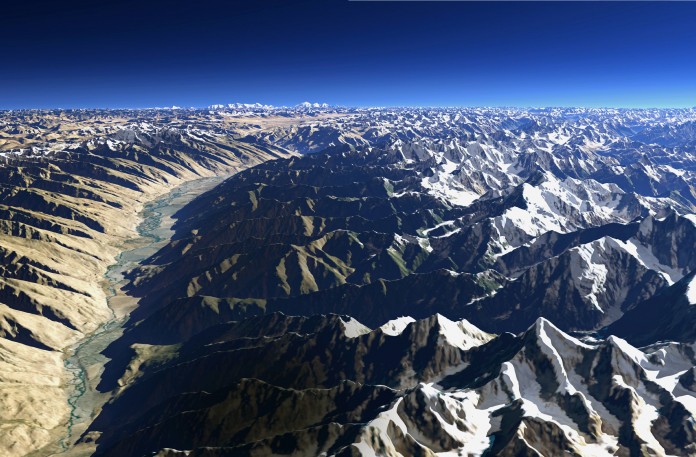

The vast glaciers of the Himalayas, Karakoram, Hindu Kush, and Pamirs, spreading across the highlands of Central and South Asia, are considered to be the globe’s third pole. Interestingly, these mountain ranges converge over Pakistan administered Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) in a unique way, making the region the undisputed core of the third pole. While mega glaciers underscore GB’s significance for regional hydrology and ecology, the region’s ability to connect Asia’s key peripheries makes it a distinctive geospatial entity. Notwithstanding growing climate change concerns and the need for a concerted climate action, India has recently been expressing an intent of confrontation vis-à-vis GB. India’s Defense Minister’s statement, “not to stop until reaching GB” seems to be an extension of the belligerent policies being adopted by the Modi government, especially towards Kashmir and Pakistan. By getting hold of GB, India could attempt to not only disconnect Pakistan and China but also get access to Central Asia and Afghanistan.

Given China’s strategic and economic interests, especially the country’s recent mega investments in GB’s infrastructure under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), Beijing has become a direct stakeholder in the region. Thus, India’s intentions of adventurism in GB might also have the motivation of killing two birds with one stone, or in other words, to give a try to its “two-front war” mantra. With general election in India due next year, the ruling party has to show to its public a disposition of a great power. Challenging both its nuclear rivals at a time would serve to win greater public mandate on the one hand, while on the other, the feat would put to test New Delhi’s partnership with Washington. For now, Washington appears to be turning a blind eye towards New Delhi’s actions in Kashmir. Any Indian actions to come eyeball to eyeball with China are likely to get the support of the U.S. Under the prevailing situation, it is imperative for Pakistan and China to take immediate measures to halt India from taking another unilateral decision and carry out any kind of adventurism in the third pole’s core.

A growing economy, popular government, and U.S. support seem to be a part of the reason behind India’s coercive diplomacy and policies. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s passive reactions emanating out of the state of confusion to decide the fate of GB and a lack of internal cohesion are other factors New Delhi appears to be capitalising on. Islamabad seems puzzled whether to constitutionally mainstream GB or keep it in a contested state to retain its international status at the United Nations. Both geography and history indicate GB to be a distinctive region and having a separate identity than Kashmir’s. The locals, wary of the Dogras of Kashmir for invading and imposing ill practices of slavery and forced labour, revolted against the Raj and acceded to Pakistan. India considers GB as a part of the then state of Kashmir and lays claim on it. Ironically, Pakistan’s inability to give constitutional status to GB and its linking the region to Kashmir are making the situation more complex. While New Delhi’s unilateral decisions accentuate complexities of an already complicated situation, Islamabad has optimistically been pushing for implementation of UNSC resolutions and arrangement of a plebiscite across the territories of GB, Ladakh, and Kashmir.

Nevertheless, keeping GB in a state of limbo does not bode well for China’s interests in the region. China and Pakistan concluded a border agreement in 1963 and ceded land to each other. During the following decade and a half, both countries constructed the strategic Karakoram Highway (KKH) — the only road link between the two countries. The recent push under CPEC to improve regional economic opportunities has brought mega investments to GB, to upgrade the KKH by constructing state-of-the-art tunnels through rugged mountains. Considerable investment is also being done to enhance power generation capacity. China must be cognizant of the fact that GB’s geographic position provides a perfect opportunity for expansion of its geoeconomic initiatives to Afghanistan and Central Asia. However, India raising a question on the sovereignty issue related to the project has added to tensions. This gives the U.S. a perfect justification not only for non-recognition of China’s economic initiative but also to discourage its European allies from taking part in it.

While this remains to be a key concern for China, India’s unilateral manoeuvring in its immediate neighbourhood seems to be a graver concern. Beforehand, New Delhi’s unilateral decision to annex Kashmir’s autonomous status has dented the delicate equation of regional stability. The ongoing India’s aggressive rhetoric of trespassing and reaching GB reeks of a country pursuing regional hegemony, or in other words, challenging China’s regional supremacy. This is coming at a time when the U.S., in its latest National Security Strategy, has committed to bolstering alliances and partnerships against China.

There is a reason Pakistan and China need to take India’s intent of confrontation seriously. Before the last general election, the Indian leadership made similar statements vis-a-vis Kashmir, and materialised what was said, immediately after the polls. Despite listening to repeated calls from the Indian leadership to change the status quo in Kashmir, Pakistani and Chinese authorities were irresponsive. Therefore, it is time for both Beijing and Islamabad to take immediate steps not only to avoid geopolitics but also to force New Delhi to use a different lens when perceiving this vital geospatial territory.

Given the significance of GB for regional ecology and hydrology, Islamabad and Beijing must make climate action a priority over geopolitics in the region. China has already been undertaking extraordinary research to preserve its glaciers and promote eco-friendly trends over ecologically sensitive places. Capitalising on this, Pakistan and China should make efforts to establish a climate-centric regional consortium of third pole countries. An agenda to declare the third pole a collective regional or global asset and make ways to declare it a nuclear weapons free zone would certainly help reduce hostilities. Furthermore, making its core, GB, a top priority for undertaking climate action, and promoting eco-friendly trends of tourism and energy generation would also benefit regional countries. This is so because it will help advance an amiable environment and avoid geopolitical volatilities. India joining this consortium would be crucial for its success. However, New Delhi’s non-participation would confirm that the country is soon going to materialise its confrontational rhetoric. In that case, Pakistan and China, while continuing efforts to preserve the environment, will have to take more drastic measures. Maybe, it is time to ensure the security of the third pole’s core. Therefore, China and Pakistan must transform their partnership into an alliance by preparing for joint air and ground defences to deter India from taking another unilateral action detrimental for regional stability. Failing to deter India from taking any kind of misadventures could result in a limited or total war over a region comprising the most glaciers outside the polar zone. Such an eventuality will certainly have global consequences.

About Author

Imran Ali

The writer is the Founder & CEO of The Karakoram Magazine. Additionally, he is a nuclear scholar fellow at the Centre for Security Strategy and Policy Research (CSSPR) and can be reached at aleee.imran@gmail.com.

Current Affairs

Unlocking Economic and Strategic Benefits: The Gwadar-Kashgar Railway Project

Published

3 years agoon

April 28, 2023

The Gwadar-Kashgar railway project is a significant infrastructure project that will connect the deep-water port of Gwadar in southwestern Pakistan to the city of Kashgar in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region. The project is part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and is expected to bring significant economic and strategic benefits to both Pakistan and China. In this article, we will explore the economic and strategic benefits of the project, as well as some of the environmental, security, financial, and geopolitical implications of the project.

Economic Benefits:

The Gwadar-Kashgar railway project is expected to transform the economies of both Pakistan and China. The project will provide a more efficient and cost-effective way of transporting goods between the two countries, opening up new trade routes and creating new job opportunities. The project will also have a transformative impact on the economy of Gilgit-Baltistan, providing new avenues for growth and development in the region. The railway line will connect China’s western region to Pakistan’s Gwadar port, giving China access to the Arabian Sea and a new trade route to the rest of the world. This will provide new markets and create new opportunities for economic growth and development.

Strategic Benefits:

The project will enhance Pakistan’s strategic importance as a key player in the region, with the potential to bring in significant investments and enhance its position as a regional power. It will also improve Pakistan’s energy security and reduce its dependence on existing trade routes that are vulnerable to geopolitical risks. The project will provide China with a new trade route to the Arabian Sea, diversify its energy supply, and enhance its strategic presence in the region. The project will also have broader strategic benefits for the wider region, helping to enhance regional stability and reduce the potential for conflict.

Security Concerns:

The Gwadar-Kashgar railway project, as a major infrastructure project, raises several security concerns. The project passes through some areas that are currently affected by security concerns, including Balochistan and Xinjiang. These areas have experienced various incidents of terrorism, separatism, and unrest in recent years, which could pose a security threat to the project.

The security of the project will be a key concern for both Pakistan and China. Pakistan has faced significant security challenges in the past, particularly in its Balochistan province, where separatist groups have been active. These groups have targeted various infrastructure projects, including the Gwadar port, which has faced security threats in the past. Therefore, ensuring the security of the Gwadar-Kashgar railway project will be a major challenge for Pakistan.

Similarly, Xinjiang, China’s westernmost province, has faced security challenges in recent years, particularly with regards to its Uyghur population. The Chinese government has been accused of human rights violations against the Uyghurs, and there have been reports of violent incidents in the region. The project’s route passes through Xinjiang, and there are concerns about the potential for security incidents in the region that could disrupt the project’s construction or operation.

Furthermore, the project could also have broader security implications for the region. The project’s proximity to Iran and Afghanistan, two countries with complex security situations, could pose additional security risks. The project could also be vulnerable to cyber-attacks, particularly given its reliance on digital technologies and infrastructure.

To mitigate security risks, both Pakistan and China will need to take steps to ensure the security of the project. This could involve deploying additional security personnel, implementing stricter security measures, and collaborating with local communities to address security concerns. The project’s planners will need to conduct a thorough risk assessment to identify potential security threats and develop appropriate mitigation strategies.

The security of the Gwadar-Kashgar railway project is a major concern, given the security challenges in the areas through which it passes. Pakistan and China will need to take proactive steps to ensure the security of the project and mitigate potential security risks. By doing so, they can help ensure the successful completion and operation of the project, and unlock its significant economic and strategic benefits.

Financing and Funding:

The cost of the project is estimated to be around $58 billion, making it one of the largest infrastructure projects in the world. The project’s funding and financing arrangements will be a key consideration, and it is likely that a combination of public and private financing will be used to fund the project.

Geopolitical Implications:

The Gwadar-Kashgar railway project has significant geopolitical implications for the region, particularly in terms of its impact on the balance of power in South Asia and Central Asia. The project will not only strengthen economic ties between China and Pakistan but also have wider implications for the region’s security and political landscape.

Firstly, the project could lead to a significant shift in the balance of power in South Asia. The railway will provide China with a direct link to the Arabian Sea, which will help it bypass the strategically vulnerable Malacca Strait and reduce its dependence on the South China Sea for maritime trade. This will enhance China’s economic and military presence in the Indian Ocean region, and could potentially pose a challenge to India’s traditional dominance in the region.

Secondly, the project will increase Pakistan’s strategic significance for China. Pakistan is already a key partner in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and the completion of the Gwadar-Kashgar railway project will further strengthen their strategic partnership. This will enhance China’s ability to project its influence in the region, particularly in the context of the China-India rivalry.

Thirdly, the project will have significant implications for Central Asia. The railway will provide China with a direct link to the resource-rich Central Asian states, which are strategically located at the crossroads of Asia and Europe. This will enable China to expand its economic influence in the region and challenge Russia’s traditional dominance in Central Asia.

Fourthly, the project could potentially exacerbate existing tensions in the region. The project passes through areas that are affected by security concerns, including Balochistan and Xinjiang, and could potentially exacerbate ethnic and religious tensions in the region. Additionally, the project could potentially heighten tensions between India and Pakistan, particularly given India’s concerns about China’s growing influence in the region.

The Gwadar-Kashgar railway project has significant geopolitical implications for the region. While the project has the potential to strengthen economic ties between China and Pakistan and unlock significant economic and strategic benefits, it also poses potential security risks and could potentially exacerbate existing tensions in the region. The project’s planners will need to carefully consider these implications and develop appropriate mitigation strategies to ensure its success

Environmental Impact:

The Gwadar-Kashgar railway project has the potential to cause significant environmental damage, particularly to sensitive ecosystems in Gilgit-Baltistan. It is important for the project’s planners to take steps to minimize the environmental impact of the project.

Conclusion:

The Gwadar-Kashgar railway project is a major milestone in the economic and strategic partnership between Pakistan and China. The project has the potential to transform the economies of both countries, as well as the wider region. It will provide a new trade route to the rest of the world, opening up new markets and creating new opportunities for economic growth and development. The project will also have significant strategic benefits, enhancing the strategic importance of both Pakistan and China and reducing their dependence on existing trade routes that are vulnerable to geopolitical risks. However, it is important to consider the environmental, security, financial, and geopolitical implications of the project as well. By doing so, we can ensure that the project delivers on its promise of unlocking economic and strategic benefits for all stakeholders

About Author

The Karakoram Magazine

The Karakoram Magazine seeks high-quality, unpublished,nonfiction, first person articles relevant to Gilgit-Baltistan and topics as varied as Geo Strategic & Economic Significance of GB, Arts & Literature, Tourism & Hospitality, Culture and heritage, Education and technology, Health & Wellbeing, Climate Change and Wildlife, Economic & Trade, Sports & Recreations, Youth & Women empowerment and Achievements of Illustrious People of GB in different fields etc.

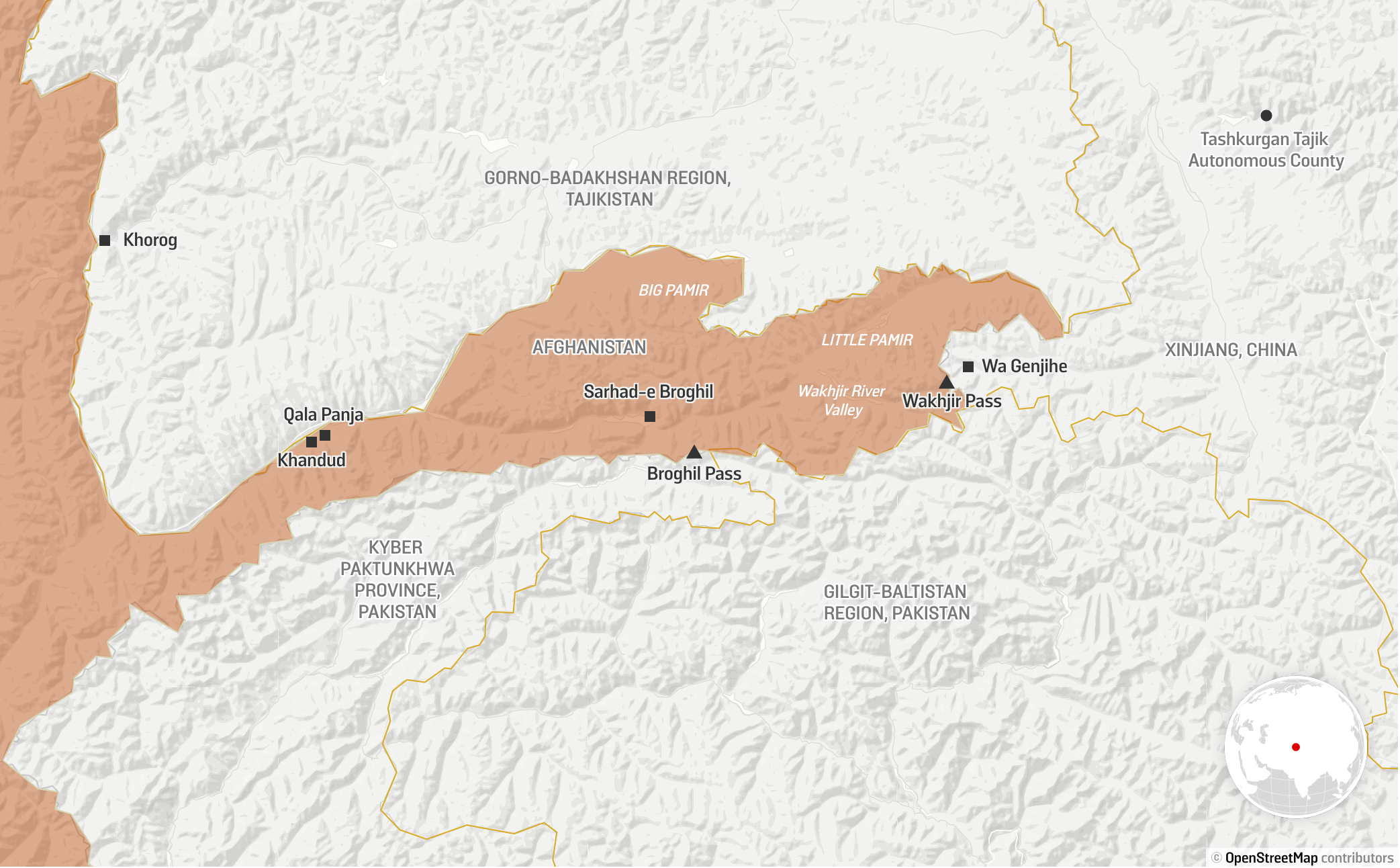

Wakhan is a strip of land in the Pamir Mountain range where China, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan share borders. The Wakhan Corridor runs North East from mainland Afghanistan to the border of China, while Tajikistan is in the north and Pakistan is in the south. The strip is 350 kilometers long and 13 to 65 kilometres wide. The total area of the strip is 10,300 square kilometers, and the population is around 15,000 individuals.

It is the place where three of the highest mountain ranges in the world converge—namely the Karakoram, Hindukush, and Pamir. The Darkot pass is a link from Yasin (GB) to Chitral (KP) and Wakhan through the Baroghil Pass. The Irshad Pass connects the Chupursan river valley, Baba Ghundi, and Gojal (Hunza) with the Wakhan Corridor. The Broghil pass of Chitral crosses the Hindukush range and connects Wakhan.

The inhabitants of the Wakhan Corridor are Wakhis and Kirghiz. The Wakhi are the Ismaili Muslims who have close links with the people of Hunza and Ghizer in Gilgit Baltistan. The Kirghiz are of Turkish origin as they descend from the Turko-Mangolian nomads of Chinese Turkestan. The inhabitants of the Wakhan Corridor, including parts of Tajikistan, Wakhan district, Kashgar, Chitral, Ishkoman, and upper Hunza (Gojal) share a common history, culture, and language. The century-long rivalry between Russia and British India for the control of Central Asian States is known as the great game. John Keay has discussed the great game played in Gilgit and Wakhan in his book ‘The Gilgit Game.

The Soviets considered Gilgit as the potential launching pad to occupy the Central Asian States from British India. The Britishers were desperate to make sure that their northern border was safe so that Russians could not sneak down through the Hindukush and Pamirs into Gilgit and Chitral.

The earliest history of Wakhan was revealed by a Chinese pilgrim, Hsuan Psung, in 644. Marco Polo passed through it to go to China during the thirteenth century. It was ruled by independent Mirs and, in 1883, the area was under the control of the governor of Badakhshan. The Silk Route from China westward passed over the north of Pamir towards Samarkand or across small valleys south of it through Wakhan, Badakhshan, and onwards to Bacteria—north of Hindukush in the valley of Oxus.

The British sent out expeditions into the area; the first one in the area was Moorcroft, then John Wood in 1937, and followed by Lord Curzan who was searching for the source of the Oxus river. Sire Aurel Stein, the famous British archaeologist, also passed through the region.

In the 19th century, the British adopted a “forward policy,” and at that time Afghanistan was an independent country but under the control of Britishers after the treaty of Gandamak. During the Great Game, the Wakhan Corridor was an independent state which acted as a buffer between the Russian and British empires. Russia claimed Roshan, Shignan, and Wakhan as a successor to the Kokand Khanate.

The Amir of Afghanistan was interested in Roshan and Shignan. However, the Britishers persuaded Amir to exchange Roshan and Shignan with Wakhan. In July 1895, the demarcation of frontiers between Russia, the British Indian Empire, and Afghanistan was carried out. The commission agreed to give all land north of Amur Darya to Russia and all land south of the Amu Darya to Afghanistan. This agreement created the Wakhan Corridor which included the district of Wakhan and went up to the Chinese territory of Xinjiang. The corridor further separated British India from direct contact with Russia.

The British constructed a fort at Kalamdarchi in the Misgar valley of Hunza at the junction of the Kilk and Mintaka pass to check Russian advances from Wakhan Corridor. After the invasion of Afghanistan, Russia established military bases across the country including a base in the Wakhan Corridor which overlooked China and Pakistan strategically.

In June 1981, Wakhan was officially handed to Russia through an agreement between Babrak Karmal and Brezhnev. After the occupation of Wakhan, Russians expelled 2000 to 3000 Kirghiz from the region. The majority of the Kirghiz population fled to Ishkoman in Gilgit under their leader Rahman Gul. I saw Rehman Gul and his companions in the Gilgit bazaar while I was in school. After spending three years there, they were airlifted to Turkey and settled in an area similar to that of Pamir.

Today again, the region has become the center of a new great game played by various players initially after the construction of the Karakoram Highway and now, with the start of CPEC. In 197, The Financial Times wrote that the Karakoram Highway was China’s new outlet to Africa and the Middle East. In the 80s, the Karakoram Highway was termed the ‘Chinese Window to South Asia’.

Now, CPEC is the focus of attention of hostile agencies. Ajit Doval, the Indian national security advisor, went on the record to say that India has a 106 kilometers long non-contiguous border with Afghanistan (Wakhan Corridor). Recently, the Indian home minister made a similar statement in Lok Sabha. However, according to Indian media, even Shah’s own ministry does not recognize any border with Afghanistan.

In 2002, India established a base at Farkhor in Tajikistan with Russian support to transport Indian relief and reconstruction supplies into Afghanistan. Farkhor is linked with the Tajik Ayni air force base where Indian air force personnel are also stationed.

There are media reports that China is planning to construct a road through the Wakhjir pass, the old Silk route, to link Afghanistan and the Central Asian States. This road in the Wakhan Corridor would end up linking Afghanistan and the Central Asian States to the Karakoram Highway and Kashgar. Any road developed after the opening of the Wakhjir pass will give China an upper hand by enhancing its dominance in the region—a clear threat to Indian interest.

The road will also help landlocked Tajikistan to get access to the Karakoram Highway as well as Pakistani ports and Pakistan’s access to mineral-rich central Asian States is likely to improve. The Chinese presence in Afghanistan will be a threat to India. And so, India along with the West is protesting against the Chinese presence in Tajikistan and the Wakhan Corridor.

China has rejected these so-called claims and confirmed that only joint training with Afghan and Tajik security forces was carried out in the past. The Wakhan Corridor can become a transit route for trade with mineral-rich Central Asian States and will open new avenues of progress and prosperity.

About Author

Muhammad Azeem Khan: Pakistan’s Number One Amateur Featherweight MMA Fighter

A Drop for a Click: The Silent Cost of Our Digital Thirst

10 Places to Visit in Hunza – Stunning Natural Wonders You Can’t Miss

Latest

-

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years ago

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years agoTraditional women’s dresses of Gilgit-Baltistan

-

KIU Corner2 years ago

KIU Corner2 years agoA Guide to LMS KIU Student Login – KIU

-

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years ago

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years agoShuqa Simple but amazing winter clothing of Gilgit-Baltistan

-

KIU Corner2 years ago

KIU Corner2 years agoEmbracing Challenges: Gul Rukhsar’s Remarkable Journey

-

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years ago

Arts, Culture & Heritage2 years agoTraditional houses Gilgit-Baltistan

-

Tourism2 years ago

Tourism2 years agoDiscover the Unparalleled Beauty and Culture of Gilgit-Baltistan

-

Opinion3 years ago

Opinion3 years agoExploring the Enchanting Astore Valley: A Paradise in the Himalayas.

-

Current Affairs2 years ago

Current Affairs2 years agoGilgit-Baltistan and the Geopolitics of the Third Pole